This week, Members of Parliament in the UK concluded that Facebook needs to face strict regulation in light of its failure to address data protection, fake news, and foreign interference on its site in a satisfactory manner. You can read our CEO’s take on this here, as well as her input that blocking sites isn’t the answer, either.

For many this step was inevitable, especially within European countries that have demonstrated eagerness to regulate and inflict penalties on Silicon Valley giants. The recent interference from Russia and Cambridge Analytica on the 2016 US Presidential elections have also served as a cautionary tale to European powers undergoing their own elections or referendums. In September of last year we saw Brussels move to impose fines on platforms that failed to remove terrorist or extremist content within an hour, with multiple ongoing committees investigating how law can impact emerging technology, and measures such as the GDPR that have had global impact on managing data online.

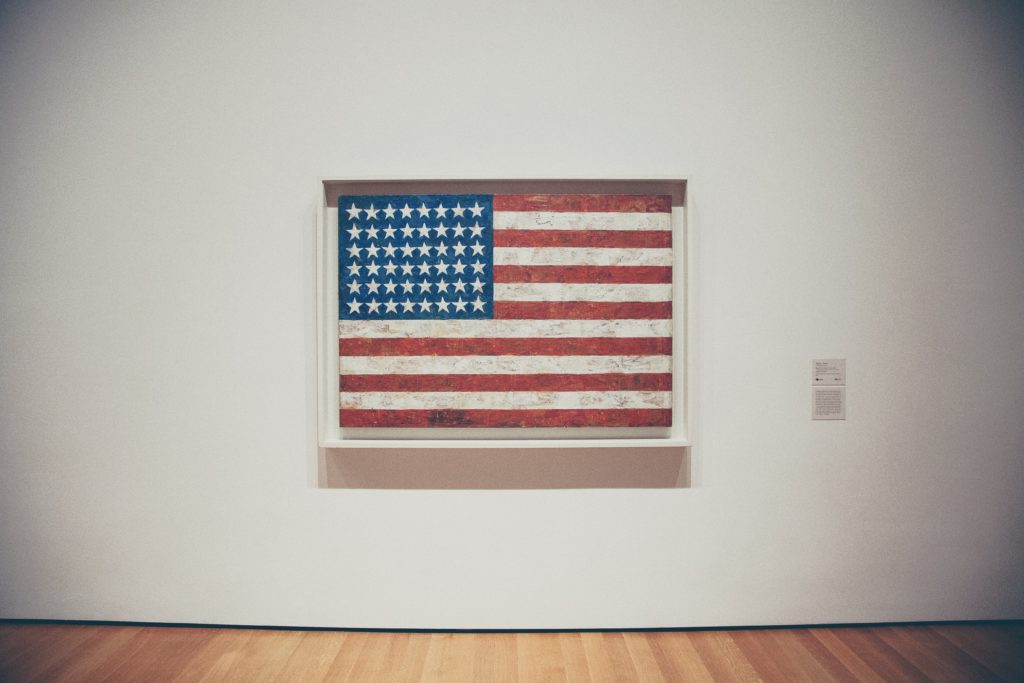

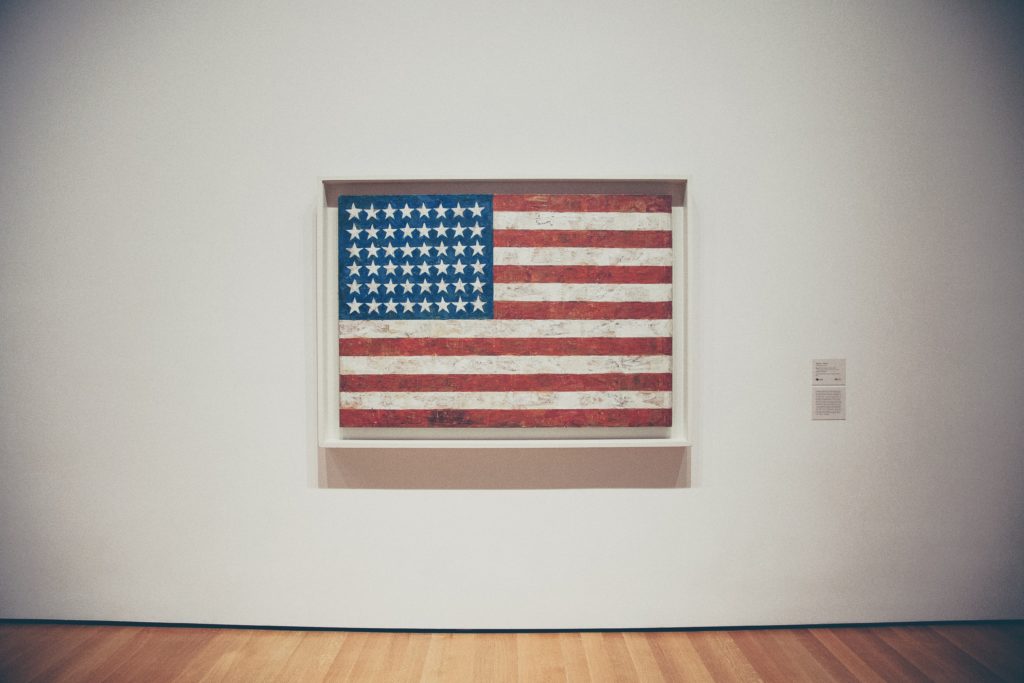

After the news broke of Russian interference in the US elections via social media platforms, the US placed a renewed focus on the regulation question as well. This has typically been met with more resistance than the discourse from European legislators. During the high profile congressional hearings that followed the elections, we saw the heads of companies such as Google and Facebook face questioning from members of congress – importantly, while Zuckerberg addressed the US Congress, he refused to travel to the UK to speak to MPs and representatives from 9 EU countries during their investigation on the same matters. Not all lines of questioning seemed particularly informed, highlighting a gap in technology and digital understanding within elected representatives and raising questions around the qualification of lawmakers to write regulation on entities they seem to know little about. Advice given to Zuckerberg during the hearings turned this on its head, stating: “You’re the one to fix this. We’re not. You need to go home and right your ship”, along the lines of the US’ long-held belief in businesses “self-regulating”. Meanwhile, Facebook has appeared open to some regulation, with COO Sheryl Sandberg stating that “we don’t think it’s a question of whether regulation, we think it’s a question of the right regulation” and with Zuckerberg’s endorsement of the Honest Ads Act that would require new transparency in online political advertising in response to the 2016 election.

While the issue of regulation is multi-faceted and complex, two elements feature strongly in common US discourse on the matter. The first element is around the first amendment, that protects freedom of speech: how would regulation negotiate that on social media platforms? In addition, who should catch the flak for harmful content published on the sites: the user who created it, or the platform who hosted it? The second element is around another core tenet of US culture: the freedom for business to innovate, with concerns raised that regulation would harm these businesses and prevent them from developing new technology and services. This was at the core of the 2015 and 2017 #netneutrality cases, whereby the Obama administration enforced regulations protecting internet service provider neutrality, that were then repealed in 2017 by the FCC’s “Restoring Internet Freedom” order in a claim to protect businesses and promote innovation.

There were also concerns around how bi-partisan potential regulation would be in a period of time when the US congress seems more at odds than ever. Would conversations on abortion be given the same restrictive treatments as pro-ana or self harm content, for example? Where can the government draw the line on what can and can’t be shared by users on a free social media platform?

The current political climate continues to widely impact or derail the case for regulation. Indeed, the renewed focus on content shared online is centered around the meddling of Russian agents during the 2016 election, and the peddling of disinformation. Just as the race for the 2020 elections is underway, similar reports are emerging that foreign actors are mounting attacks on democratic candidates and spreading fake news. This is the angle that is likely to draw most attention ongoing: the political repercussions of such a use of social media platforms, rather than the roles of the platforms themselves.

As the Washington Post reported after the hearings last year, while lawmakers typically agree this is an important topic, any legal and federal action is unlikely any time soon. This remains true as the political and legal discourse in the US continues to be overshadowed by investigations into the president and by lawmakers unwilling to compromise on party lines. It’s more likely that change to social media platforms will stem from EU regulation: Silicon Valley have been taking steps to comply with the EU, with Zuckerberg confirming that “all the same controls will be available around the world” and that they’re dedicated to leading the way in terms of keeping their platforms safe, though, as we’ve seen, not to EU standards.